How a comic book artist discovered GB Studio and created games that challenge the "just world fallacy" while embracing the Game Boy's limitations as strengths.

Ben Jelter never expected to finish his first video game in a single day. But on a December evening in 2019, rushing to show friends at a drawing workshop, he discovered GB Studio, a tool that would transform him from a frustrated would-be game developer into one of the most thoughtful indie creators working with Game Boy hardware today.

"I made that game in a day in GB Studio," Ben recalls. "It was just messing around to see if I could use the program. The program was so approachable that I was able to quickly make something because that evening I was going to a drawing workshop with some friends, and I wanted to actually be able to show them something I made on a Game Boy."

That spontaneous mini game jam marked the end of a decade-long struggle. Since 2009, Ben had started numerous game projects but never managed to complete one. As a comic book artist and art instructor without programming skills, the complexity of traditional game development tools had proved overwhelming. GB Studio changed everything.

Watch the full interview on YouTube

The Comic Book Foundation

Ben's path to game development began in the world of sequential art. As a comic book artist who had spent years crafting long-form narratives, he brought a unique perspective to game design: one focused on handcrafted experiences rather than algorithmic content generation.

"Making comic books, especially very long comic books, involves planning a very large scale project and then working on it for a year or two," he explains. "I think that lends itself very well to working on video games. You know how to handle a long-term project."

But games presented new challenges. Unlike the linear progression of comics, where Ben worked "like a robot," scripting everything before drawing page by page, games required identifying core systems and ensuring they functioned before moving forward. This shift from linear storytelling to systemic design would prove crucial in shaping his game development philosophy.

Why Game Boy? The Power of Constraints

When asked why he chose Game Boy development over more versatile engines like Unity, Ben's answer cuts to the heart of his design philosophy: workflow and limitations breed creativity.

"The brutal truth is Unity is way more complicated," he admits. "I'm a big workflow person. I don't use Photoshop; I use Clip Studio Paint because I can rearrange all my palettes and shortcuts and even make my own tools that I can access with keyboard shortcuts I made up."

But there's a deeper reason tied to his childhood. While friends had Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis systems, Ben's parents bought him a Game Boy, partly due to the single TV limitation, partly from anti-consumerist concerns, and partly to keep him active outdoors. This early relationship with the portable system created a special connection that would influence his creative choices decades later.

"Game Boy is to me the most special system," he reflects. The constraints weren't just nostalgic. They were strategic.

The Machine: Challenging the Just-World Fallacy

Ben's breakthrough game, "The Machine," exemplifies his approach to meaningful game design. Rather than creating another power fantasy, he built a dystopian experience that deliberately subverts player expectations.

"The Machine is fundamentally a game about life," Ben explains. "In life, you can make decisions that ruin your life, and you can make decisions that set your life on a completely different course. But The Machine is a dystopia, so the theme of the game is you can make whatever decisions you want, and you can do better or worse, but none of the decisions you make are going to change the way that the machine works."

The game's central mechanic reflects Ben's critique of the "just-world fallacy": the cognitive bias that leads people to believe the world is inherently fair and people get what they deserve. In The Machine, good actions often lead to bad outcomes, while selfish choices frequently result in personal success.

"If you are bad, good things happen to you, and if you're good, bad things happen to you. That's the core rule of The Machine," Ben states. "I feel like that reflects life more accurately than most fiction."

This inversion of typical game morality systems serves a larger purpose: forcing players to confront uncomfortable truths about power structures and social mobility.

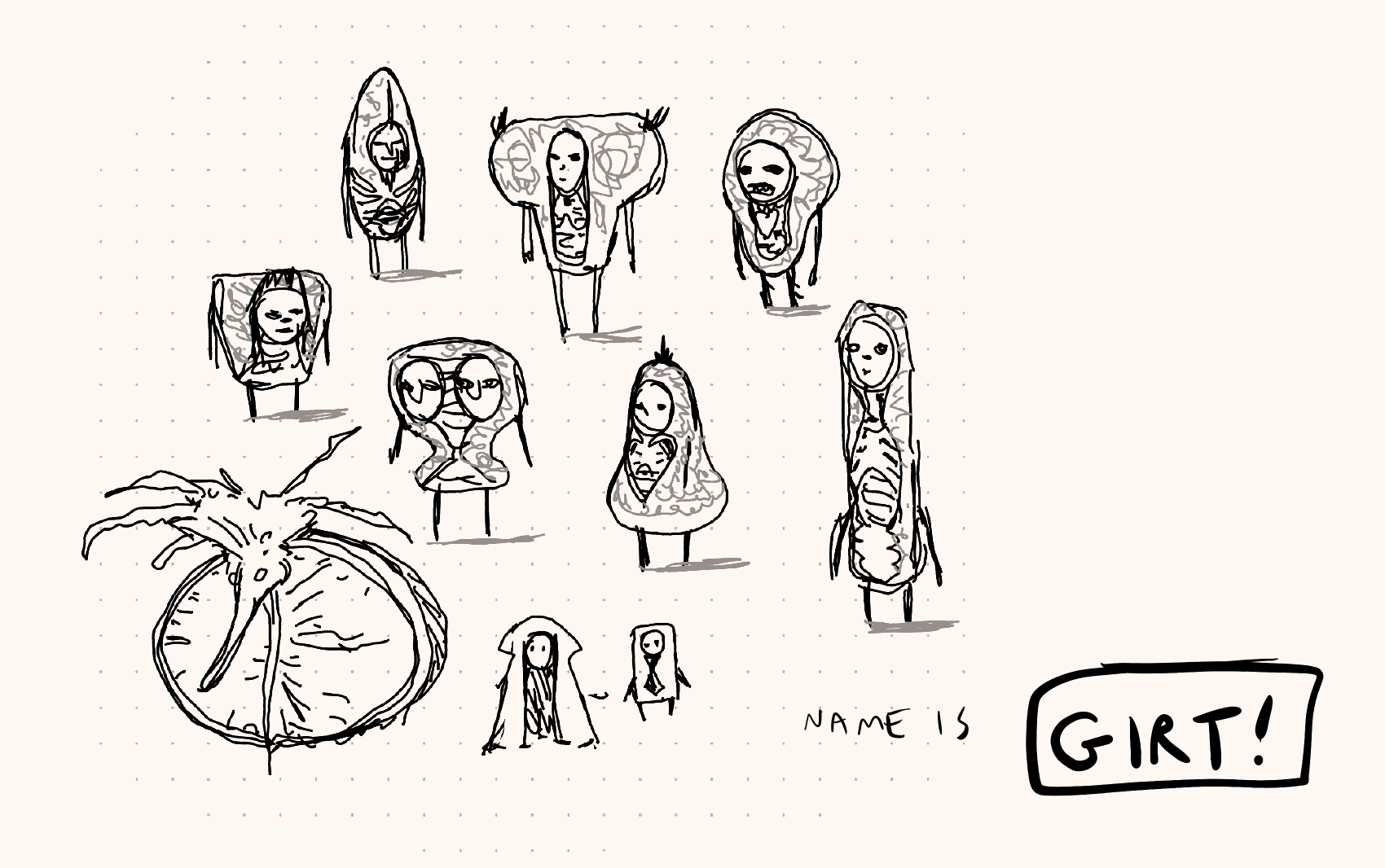

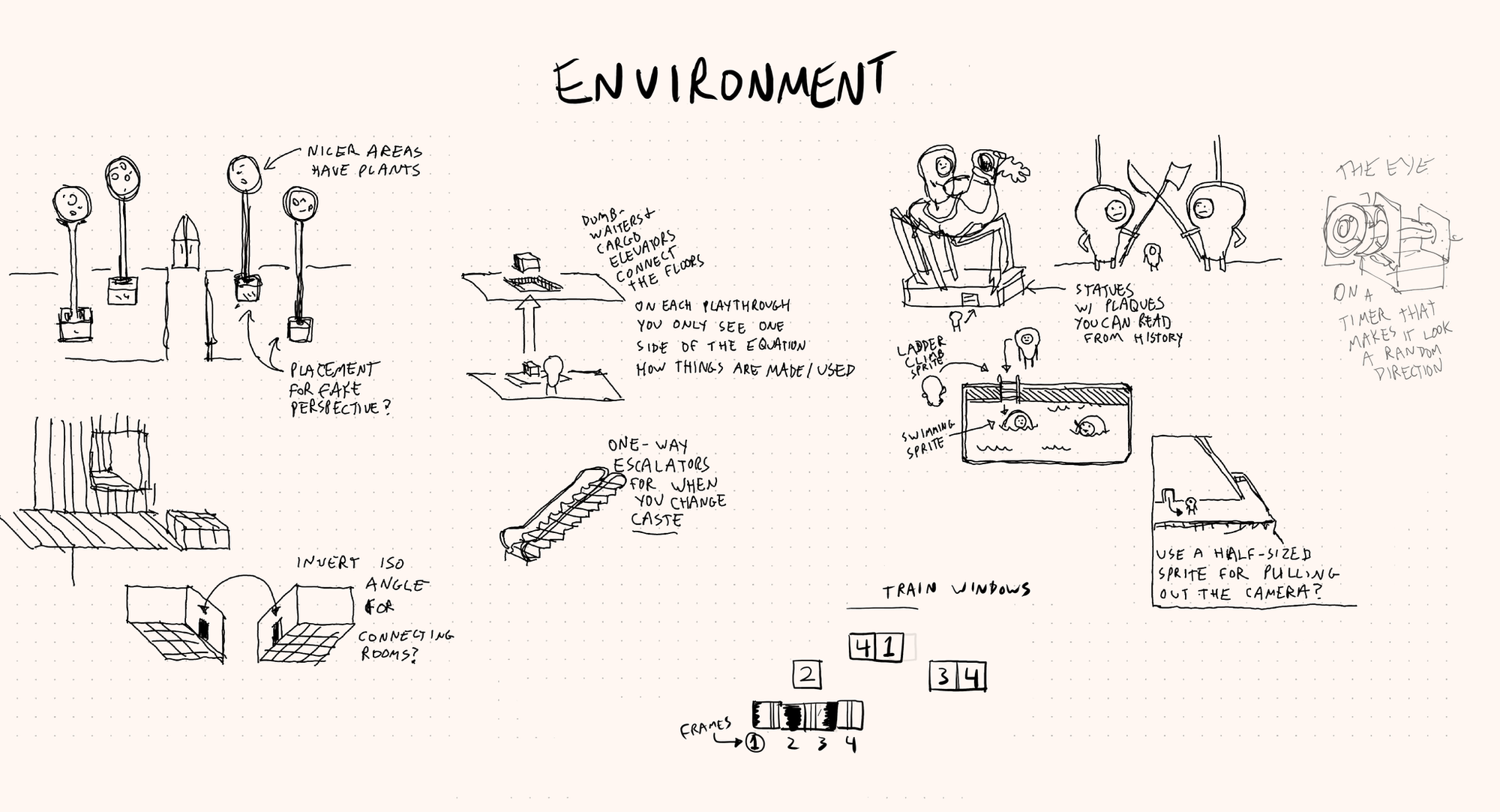

From top-left: The Machine physical copy with all extras, development sketches of characters, characters for printed manual, environmental sketches

The Evolution of GB Studio

Ben's relationship with GB Studio has evolved alongside the tool itself. He started with version 1.1, when the program was remarkably simple—drop a PNG file with specific dimensions, and the program would automatically create animated sprites. But this simplicity was also its strength.

"Everything is a two-frame animation. You just draw two pictures of the actor facing down, two pictures facing up, and two pictures facing right, and then it will automatically populate. Then you can immediately run a build and walk around as that character. It's really fun."

As GB Studio has grown more powerful through versions 2, 3, and now 4, Ben has watched it transform from a constrained creative tool into something approaching a full game development suite. While he appreciates the added capabilities, he maintains that newer developers should start with earlier versions to understand the fundamentals.

"If you're young or really a beginner when it comes to game development, I do recommend checking out GB Studio 1.2 because it is a lot simpler and forces you to make a lot less decisions or build a lot less groundwork for your game before you can just make it."

Handcrafted vs. Hamster Wheels

Ben's games stand out in an industry increasingly focused on player retention metrics and time-padding mechanics. His philosophy centers on respecting player time through carefully crafted experiences.

"The main thing that I don't like in video games is the way that they're so repetitive and predictable because the people that made them don't value your time," he says. "You do something and nothing happens, and then they tell you to do it another 20 times."

Instead, Ben advocates for games that feel handcrafted, where each element serves a narrative or mechanical purpose. This approach requires more development time but creates more meaningful experiences.

"I tried to make the game handcrafted in a way where each thing the player sees is something that I made, instead of just hamster wheels. If it feels to me like a hamster wheel, I don't want to make the player do it."

The Discipline of Single-Threading

Ben's work ethic reflects his commitment to focus and craftsmanship. Before his son was born, he would work over 12 hours a day using a strict timer system: 52-minute focused work sessions followed by 8-minute breaks.

"I get distracted easily, so I would have timers that I would set for work sessions where I could do nothing but work on the game," he explains. "A lot of people think they are [good at multitasking] but are just also bad at multitasking. I don't ever try to multitask—I guess on Game Boy it would be called single-threaded."

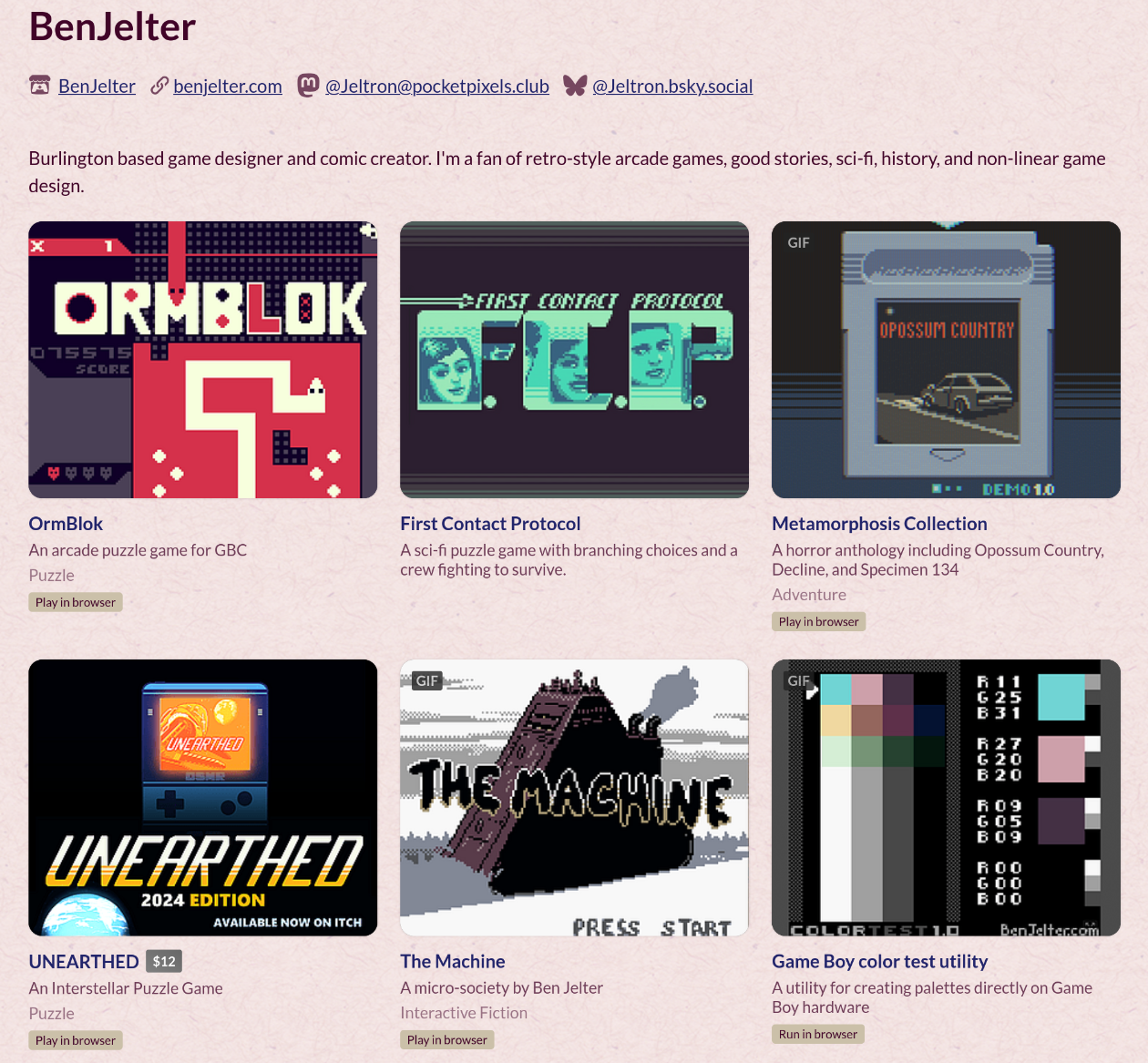

This approach has enabled him to release multiple games at an impressive pace:

- The Machine (2022), with music by lunchz

- Metamorphosis Collection (2024), with music by lunchz

- Unearthed (2024), with co-creator Gumpy Function, music by lunchz

- First Contact Protocol (2025), with music by Jonnie Baker

- Ormblok (2025), with co-creator Technofantasy, music by Robotmeadows

Each explores different themes while maintaining his commitment to meaningful interactivity.

First Contact Protocol: Exploring Human Dynamics

Ben's latest game, First Contact Protocol, shifts focus from societal critique to interpersonal dynamics. Players control a small alien creature infiltrating a generation ship, influencing relationships between six crew members with competing motivations.

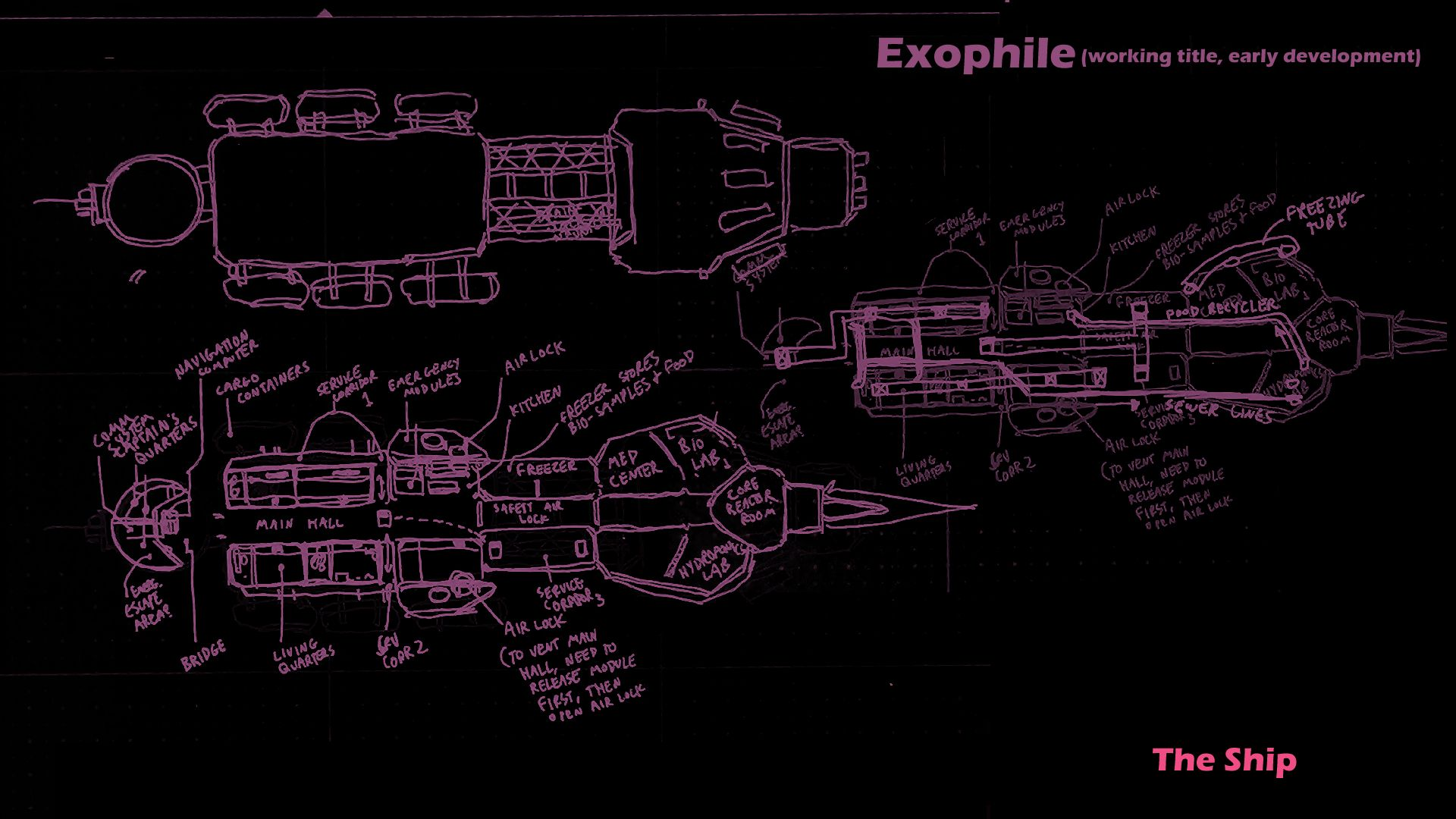

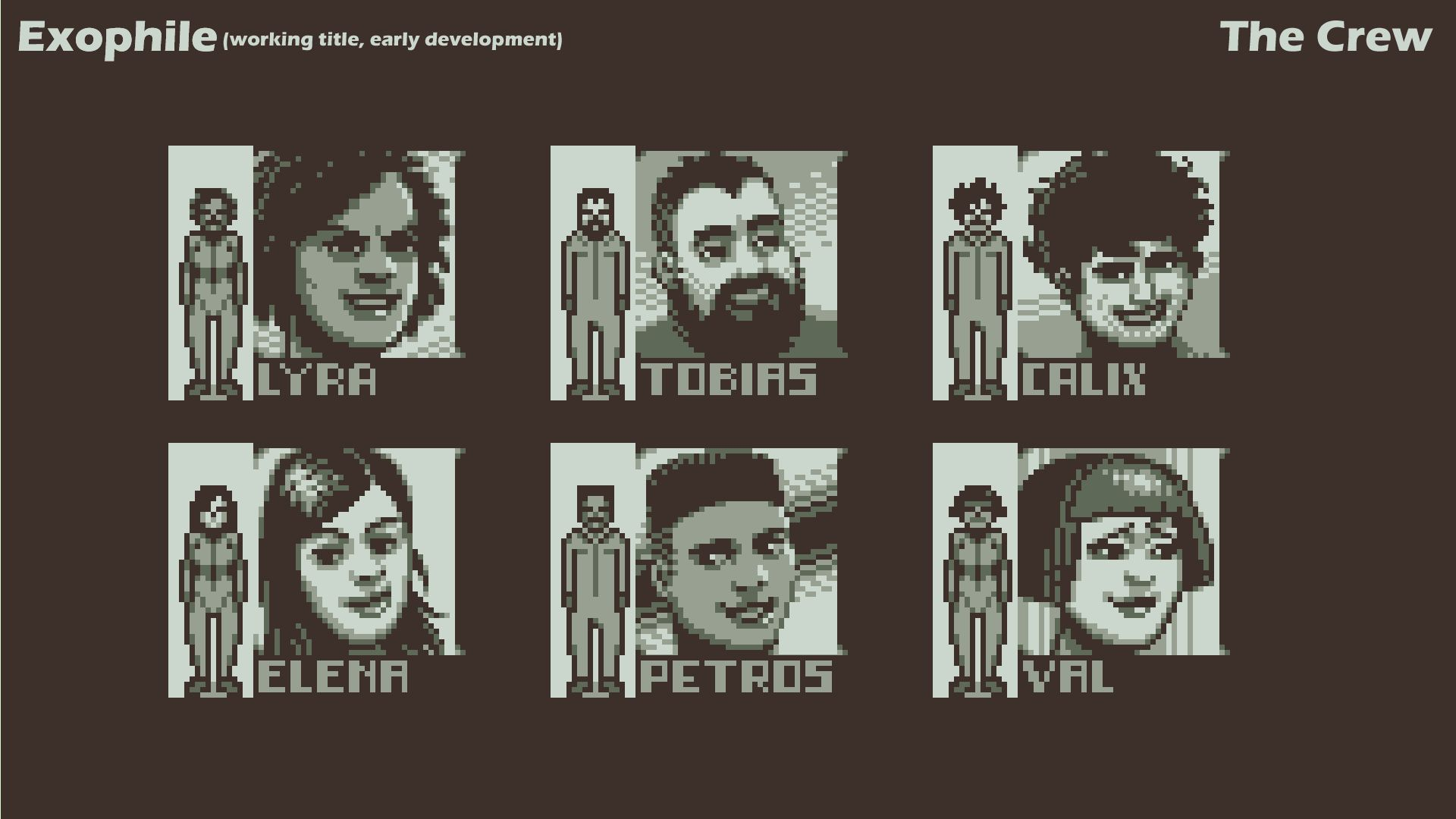

Early proposal sketches, while the working title was still "Exophile"

"I thought, what if there's a game about the complex, interconnected nature of relationships between human beings, but on a smaller scale?" he explains. "Some people's goal is in direct opposition to another person, so those people are less likely to like each other, and you can sort of influence the outcome by things that you do."

The game explores the butterfly effect, how small actions early in the experience can have dramatic consequences by the end, especially when humanity's future hangs in the balance.

The Future of Constrained Creativity

As GB Studio continues to evolve and the homebrew Game Boy scene grows, Ben represents a particular approach to game development that embraces limitations as creative catalysts rather than obstacles to overcome.

"Limited options are like an accelerant for game development," he says. "It helps you get to the part where you're making the game instead of endlessly spinning your wheels."

In an industry often focused on technical advancement and feature expansion, Ben Jelter's work serves as a reminder that meaningful games can emerge from the most constrained platforms, if developers approach those constraints with creativity, discipline, and respect for their players' time.

For aspiring Game Boy developers, his advice is simple: start with GB Studio 1.2, make something small, then graduate to the latest version. But most importantly, focus on crafting experiences that justify their existence in the world.

"I don't think that we should just make things for the purpose of having made them and just to turn around and make money off of them. I feel like we should try to advance human culture."

You can find Ben Jelter's games at benjelter.itch.io and learn more about GB Studio at gbstudio.dev. His games The Machine, Metamorphosis Collection, and First Contact Protocol are available digitally and in physical cartridge form through various publishers.