Earlier this year we sat down with Erik Andersen, developer of the innovative Japanese learning puzzle game So to Speak.

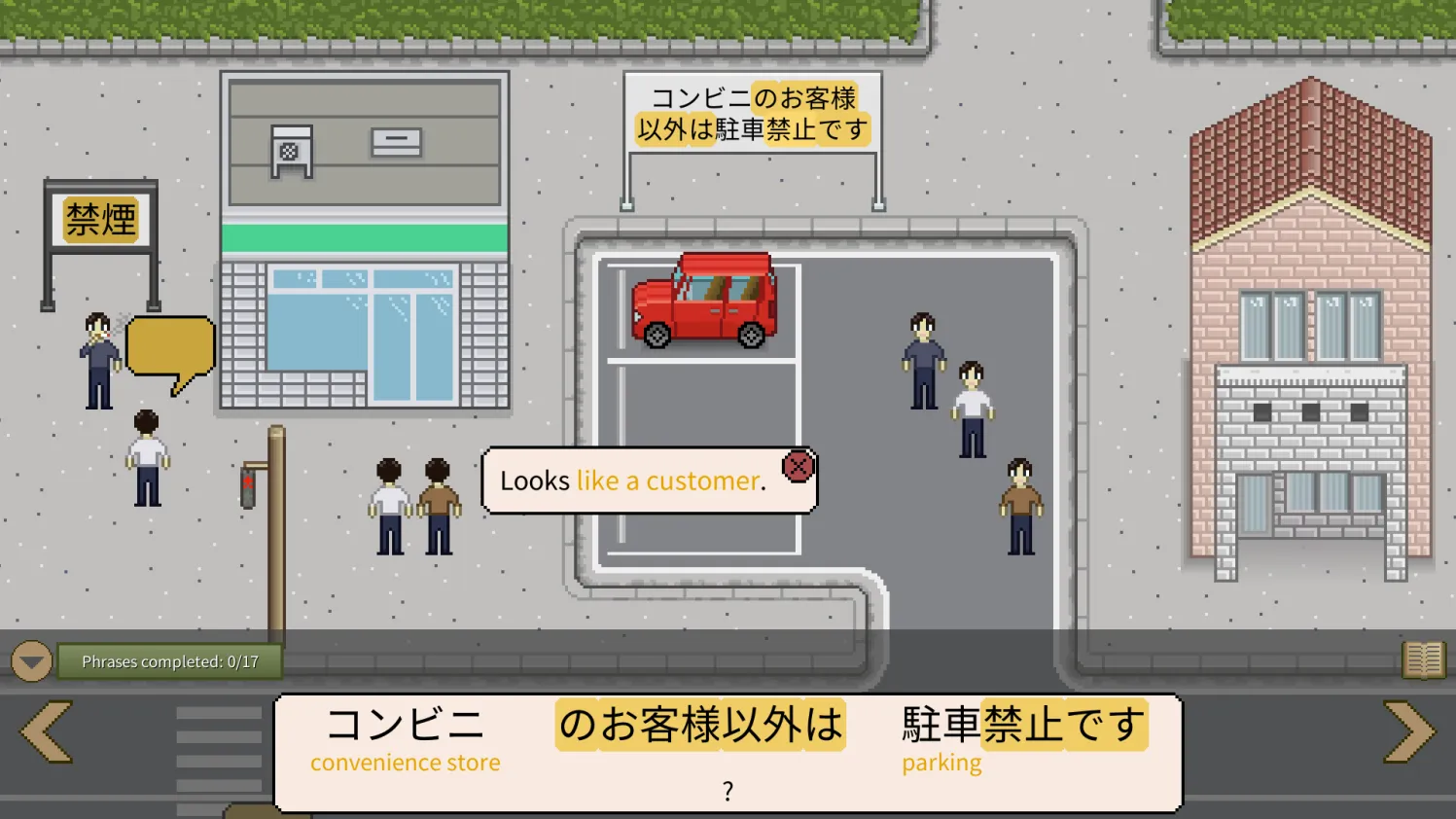

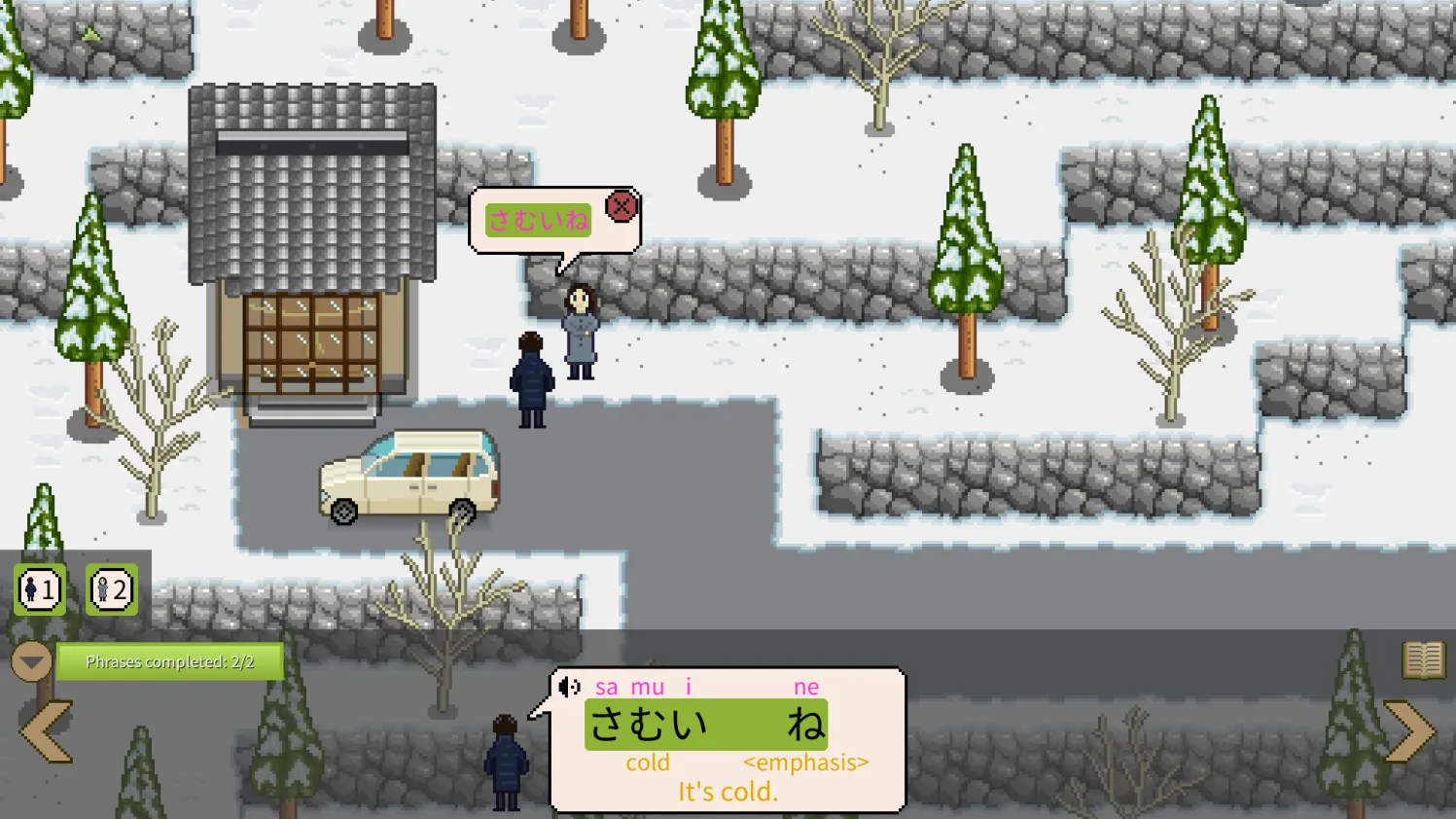

So to Speak drops players into a 2D simulation of Japan where they must decipher the meaning of Japanese words through context clues and visual connections. Players drag Japanese text onto corresponding objects or English descriptions, learning naturally through discovery rather than memorization. Unlike conventional language apps that rely on flashcards, the game presents practical vocabulary that travelers would actually encounter: entrance and exit signs, bathroom markers, and everyday conversation snippets.

Our interview with Erik reveals the story behind this innovative educational game. What started as a personal mission became a six-year solo development journey that transformed an academic researcher into an indie game developer.

From Academic Research to Indie Development

Erik's path to game development was anything but conventional. While pursuing a PhD in graphics research, he got his first taste of educational game development working on "Refraction," a Flash-based puzzle game for learning fractions that gained popularity on Kongregate.

After his doctorate, Erik taught video game design at Cornell University while researching educational games. But academia's emphasis on grant proposals didn't align with his creative ambitions. "I didn't really like academia in general. I like teaching but I didn't like writing grant proposals," Erik explains.

The catalyst for So to Speak came from his personal life. Married to a Japanese woman and raising a bilingual daughter, Erik experienced firsthand the frustration of traditional language learning methods. "I'm convinced that there's really no other skill that you can invest so much time into and still be so bad at," he reflects on the challenges of language acquisition.

The game's central mechanic emerged from Erik's real-world experiences in Japan. "I've been in train stations in Japan seeing signs like exit or bathroom and sometimes I try to figure out what is this talking about. I realize that this is not so bad - I kind of like it."

This observation became the foundation for So to Speak's approach to learning. Unlike conventional language apps that provide immediate translations, the game requires players to puzzle out meanings through contextual clues - much like deciphering unfamiliar signs while traveling.

The game presents practical vocabulary that travelers would actually encounter: entrance and exit signs, bathroom markers, and everyday conversation snippets. This focus on making sure that you learn something useful immediately sets it apart from textbook approaches that often start with abstract grammar concepts.

So to Speak started as a two-year project but ultimately required nearly six years of development. The extended timeline reflected both the scope of Erik's ambitions and the learning curve of solo development.

Two years into development, Erik hit a major roadblock. He had initially started in Python using Pygame for rapid prototyping, but eventually hit distribution limitations and made the difficult decision to completely rewrite the entire game in C# using MonoGame. "I had to rewrite the whole game," Erik recalls, though he used the opportunity to fix fundamental design issues as well.

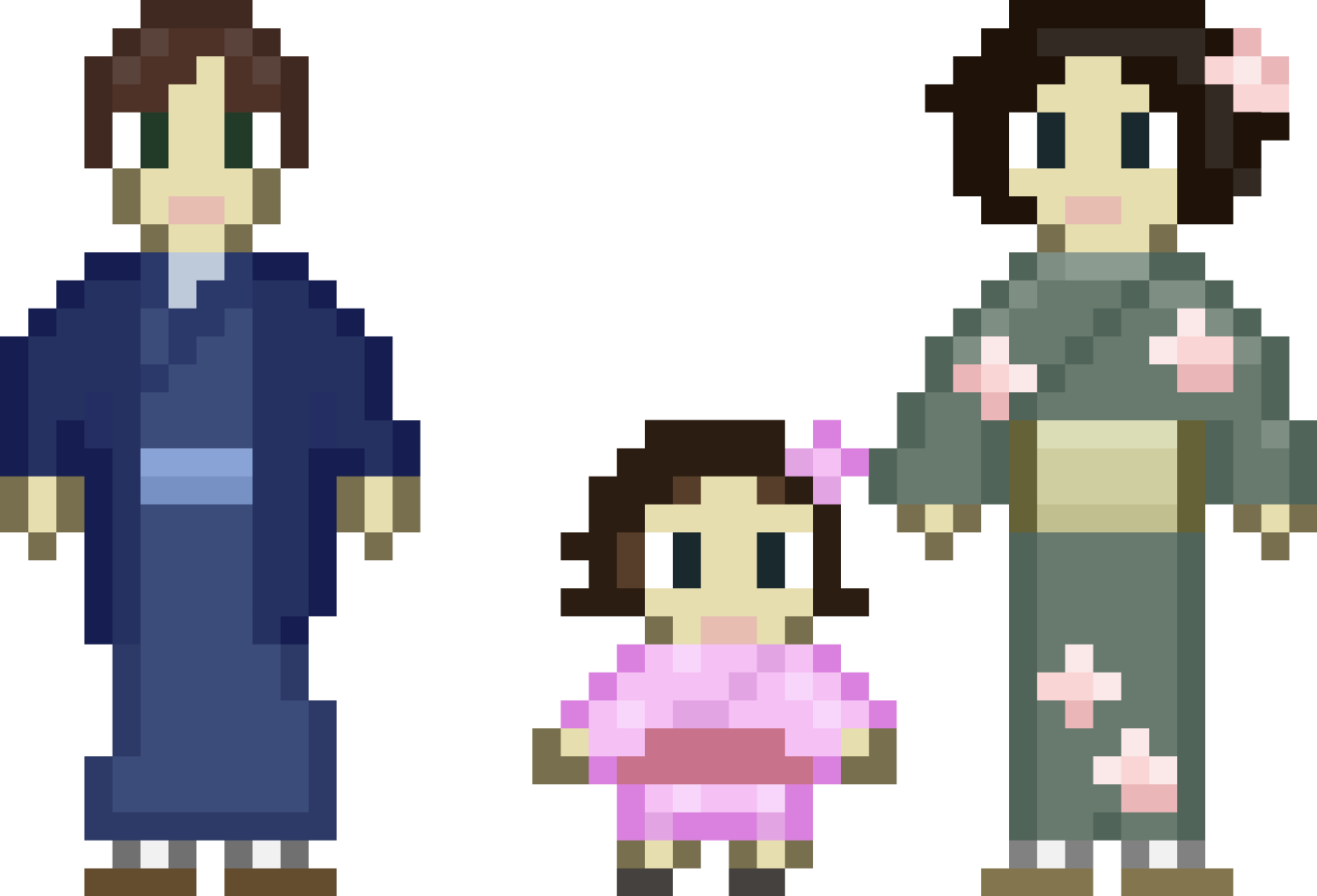

Perhaps most remarkably, Erik taught himself pixel art from scratch through YouTube tutorials and persistent practice. Drawing inspiration from Stardew Valley, he developed his own art style over the six-year period. One innovation was making building interiors visible through windows, helping players understand context - like identifying a café by seeing people drinking coffee inside.

The Importance of User Testing

Throughout development, Erik conducted regular playtesting sessions that proved crucial to the game's design. One early revelation challenged his initial assumptions about language learning games.

Originally inspired by games like Heaven's Vault (where players decipher a fictional language), Erik implemented delayed confirmation for player guesses. But testers absolutely hated this approach. "Players really want to know right away if their guess is correct," Erik discovered.

This feedback highlighted a key difference between fictional and real language learning. With invented languages, delayed confirmation can build suspense. But when learning an actual language for practical use, immediate feedback becomes essential for building confidence and accuracy.

The game's interface also underwent major revisions based on user feedback. The original design featured intrusive popup menus that blocked the game world. Erik's friends suggested the elegant bottom workspace that appears in the final version, keeping interaction elements accessible without obscuring the scene.

Art progression from 2019 to 2025

Building a Comprehensive Learning Experience

The final game includes over 650 Japanese words covering practical topics like telling time, counting, location descriptions, and family relationships. Erik deliberately mixed all three Japanese writing systems (hiragana, katakana, and kanji) from the beginning, reflecting real-world usage rather than the graduated approach of most textbooks.

The game features eight different voice actors - friends and family members who contributed to authentic pronunciation. Erik's brother Greg composed the lo-fi background music that perfectly complements the relaxed puzzle-solving atmosphere.

Real-World Validation

Released on March 31, 2025, So to Speak has received positive reviews and active streaming on Twitch. Most importantly for Erik, players report recognizing words from the game during actual trips to Japan - validating his core hypothesis about contextual learning.

"I have some friends who went to Japan after they played a version of it and they actually recognized a word on a sign there," Erik shares. The game represents a successful experiment in contextual learning - one that other educational developers might learn from.

As Erik puts it, "People naturally have that ability and that mechanism" for learning through context, drawing parallels to how we all naturally acquired language as children. So to Speak proves that educational games can be both pedagogically sound and genuinely engaging by respecting players' intelligence and natural pattern-recognition abilities.

Check out our full interview with Erik on YouTube:

Or listen on our podcast:

So to Speak is available now on Steam for PC, Mac, and Linux.